Change

There’s no doubt the industry has to change toward a more sustainable future. And there’s no doubt that this won’t be without casualties. Similar to air travel, meat consumption, and video streaming, sustainable growth can paradoxically only be achieved with less consumption, in a more conscious manner.

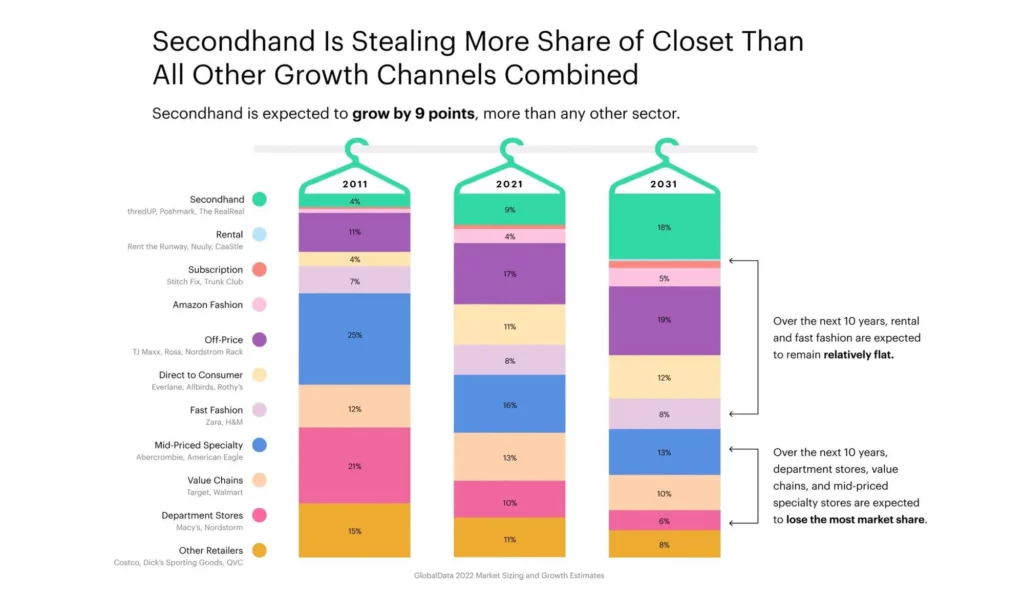

Gen Z is no longer piling up clothes in their wardrobe. As a matter of fact, UNIQLO, ThredUP, and others are giving people for the first time ever a reason to clean out their closets more often. The question remains: who’s gonna fill this new, vacant closet space?

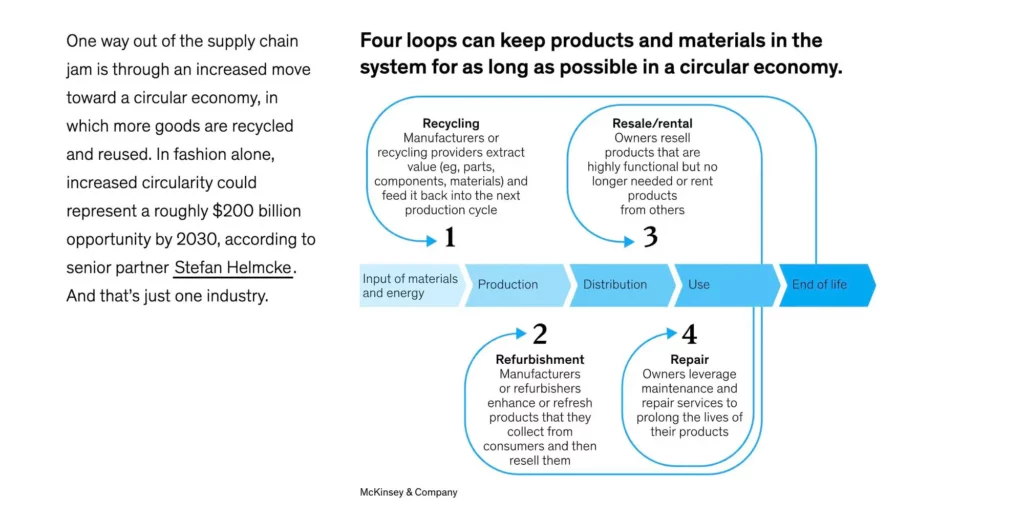

Opinions are divided. McKinsey summarized four ways for manufacturers to tap into this more conscious customer behavior — and recuperate garments or fabrics in times of supply chain jams.

Incumbents are now placing their chips on the table, with most of them openly experimenting on multiple fronts. However, it looks like almost all of them seem to believe their future lies in rental.

Making the numbers work

Depreciation vs sense of ownership

Fashion rental company Rent the Runway once reported their “gross profit excluding product depreciation,” which removes the cost of the clothes being rented out from the cost of goods sold. Though making the shift from selling to rental — read: no longer transferring a sense of ownership to your customer — will inevitably accelerate depreciation. This insight incentivised some retailers to look into more durable materials, to extend the garment lifecycles.

Time will tell whether any adaption to this business model will be as powerful as the business model that platforms like Vinted carry out. The main idea: instead of renting out, why not leave the ownership with the person wearing it, who then has every incentive to keep the garments in good condition for a potential third- or fourth-hand sale.

London-based startup Bandi is trying to address the same issue by connecting “clothing twins” with each other. Their hypothesis is that an ongoing relationship would help fostering a sense of ownership.

Two-way shipping

Aside from a higher rate of depreciation, rental has a second unfair disadvantage to deal with. Free shipping has become an expectation in e-commerce, making it harder to pass on the costs to the end customer.

Publicly listed companies have a history of using “creative accounting” for this, too. Modified versions of the EBITDA are deployed to cover up the ongoing struggle to make a profit on core activities. British e-retailer ASOS, to name one, once noted it had reclassified delivery costs from cost of sales to operating expenses. “To reflect their increasing deployment as a marketing expenditure”, they stated.

In rental, shipping is guaranteed to be twice as high (back and forth) and gets assessed in the mental accounting of customers against a lower perceived value (short-term rental vs. a sale) compared to traditional e-commerce. This too, should be seen as a major unfair advantage for Vinted and the likes.

Dressmate, founded in 2016 as a peer-to-peer fashion rental platform for college students, became oversaturated with fast-fashion apparel that was too cheap to justify the shipping (and cleaning) costs. They ended up pivoting into a marketplace for peer-to-peer apparel sales.

H&M Group is exploring whether it can get its rental customers to keep their garments for a longer period (at least a season). This, however, opens up a multitude of new challenges. Like, who should own the washing cycle then?

Other platforms try to overcome this by getting customers to order multiple items at the same time, or by focusing on higher-end garments. Needless to say, those strategies make rental less accessible on a mainstream budget.

What can incumbents do?

Maybe you figured already that traditional retailers can leverage their network of physical stores to tackle this cost handicap. Though real estate comes at a cost, too. Furthermore, we cannot neglect the higher inventory needs and lower rotation rate that can be expected in such decentralised setup.

But while this article pointed out some serious treats and concerns for traditional retail moving forward, it’s not all bad. Sure, the fashion industry has to change to adopt to a changing market and a changing planet. But by creating long-lasting garments in combination with highly desirable brands, there can never be a thriving second-hand market without them.

Incumbents will always remain relevant at the inception of the product lifecycle and, if they do it well, they can also participate in the value that is generated down the line. Think of building trust in peer-to-peer trading, support retrofitting of pre-loved items, or taking care of repairs, refurbishment and recycling. One of many examples is the partnership between vintage retailer Beyond Retro and e-tailor — not e-tailer — Sojo. They have the joint goal of making every second-hand sale a perfect fit, boosting circularity and reducing return rates.

For rental, the focus should be on renting out garments with a higher (perceived) value and for more occasional events, like Patagonia’s “Don’t buy this ski jacket. Rent it instead” campaign.